Tea is not just a beverage; it's a global phenomenon that has quenched thirst and soothed spirits for thousands of years. The story of tea from a medicinal leaf to a worldwide staple drink is a story of domestication and cultivation that began more than 4000 years ago. Today, tea grows in more than 52 countries in tropical and subtropical climates. It has become a significant crop for many developing nations, with China and India leading as the top producers worldwide.

The heart of tea's diversity lies in its countless varieties, each contributing its taste, aroma, and flavor to the world of tea. The major varieties, Camellia Sinensis and Camellia Assamica, are well-known in the tea community for the wide array of tea flavors and textures they give birth to. However, beyond these popular varieties exists a realm of lesser known species that play a crucial role in the rich and varied world of tea.

This article aims to explore the depth of tea varieties, from the renowned to the rare. We'll dive into each variety's history, characteristics, and unique qualities, offering a comprehensive look at the plants that create our beloved beverage. At the same time, we hope to contribute to a better understanding of the tea plant and create a more vibrant and detailed representation of the rich world of flavors, aromas, and tastes induced by the vast array of tea varieties out there.

Tea taxonomy – why the name matters

Before diving into our subject today, it's important to understand the classifiers that differentiate among different types of tea plants. We will discuss one plant—the tea plant—which, however, exists in many variations. So, let's start with some terminology first.

We will mostly talk about the tea plant called Camellia Sinensis. The complete plant classification includes division, class, subclass, order, family, genus, and species. In our case, we will also add variety and cultivars. Knowing this, here's how the tea plant looks:

Division -> Magnoliophyta

Class -> Magnoliopsida

Subclass -> Dilleniidae

Order -> Theales

Family -> Theaceae

Genus -> Camellia

Species -> Sinensis

So, we're down to the Camellia Sinensis species, which is largely the most popular (99% of the varieties coming from it) and one of the most commercially significant species in the world.

The following classifiers in the plant taxonomy are the variety and the cultivar. What's the difference? In a nutshell, a variety is a naturally occurring plant species that forms without human intervention. A cultivar is a plant species that forms through human intervention (i.e. by inbreeding and crossbreeding techniques).

The name "cultivar" is an abbreviated form of "cultivated variety", or a variety created with human help rather than through a spontaneously occurring mutation in nature.

So, when we refer to different tea plant names, we follow the classification: genus—species—variety—cultivar. In this way, a famous Japanese cultivar, Yabukita (used for Hei Cha production in Japan, among other things), would be called Camellia Sinensis var. Sinensis "Yabukita." Here, Camellia is the genus, Sinensis is the Species, var. Sinensis is the variety, and Yabukita is the cultivar.

The Cambodian connection

There are currently two major tea varieties in the world: the Sinensis (small-leaf) and Assamica (large-leaf) varieties. Essentially, 99% of the world's tea production comes from them.

There is information about a third tea type, the Camellia Cambod or Cambodi, sometimes called medium leaf variety. According to some sources, it is the third naturally occurring tea variety after the Sinensis and Assamica. Its origins are traced in Cambodia (hence the name), where it grows in a wild state. There is a lot of confusion on the botanical origin of the Cambodia variety. Britannica says it's a variety of the Camellia Sinensis species, with a Latin name C. sinensis, variety Cambodiensis. Others, like Oxford, believe it to be an Assamica subspecies, called Camellia Assamica sub sp. Lasiocalyx. Recent research from 2016 explored the genetic differentiation among selected groups of tea from China (Sinensis and Assamica variety), India (Assamica variety) and Cambodia (Cambodi variety). The results proved that Cambodi variety shows mixed genetic composition of the Assamica tea varieties found in China and India. Thus, the Cambodia tea variety appears to have originated through hybridization between these tea types and should not be recognized as a naturally occurring taxon. Therefore, the researchers classified Cambodi tea as a subspecies of the Assamica variety.

Nowadays, the Cambodi tea is mostly grown locally and not used for large scale commercial tea cultivation.

Camellia Sinensis and Assamica – where it all started

Camellia Sinensis var. Sinensis, often simply called Sinensis, comes from the Latin word for "Chinese". This small-leaf variety is a cornerstone of tea culture in the countries that served as a cradle for the birth and development of tea culture – China, Taiwan, and Japan. The small-leaf variety of Camellia Sinensis var. Sinensis is also the backbone of some of the world's most cherished green teas, oolong teas, and certain delicate black teas. The Sinensis variety grows as shrub-like plants, yielding leaves with subtle, delicately aromatic flavors distinct from those produced by its cousin, the Assamica variety.

This variety adapts well in colder climates and thrives in high-altitude regions with significant changes in weather and temperature. Some sources suggest that the Sinensis variety originated from the Assamica variety. As it migrated to the northern tea-producing regions, Sinensis significantly transformed its look and feel. It developed its smaller, more delicate leaves known today through natural adaptation and cultivation by tea growers. When processed into dry tea, it offers a lighter, aromatic profile that distinguishes the teas of China, Japan, and Taiwan.

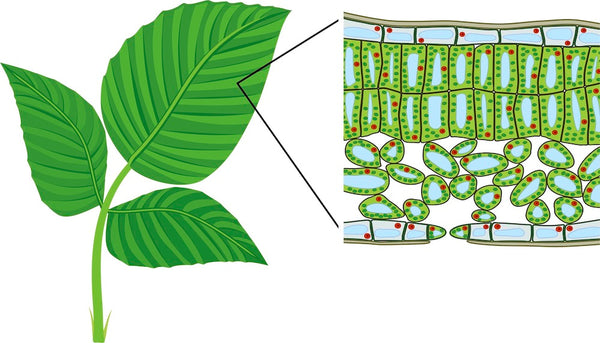

To understand this variety's influence over the teas produced by its leaves, let's look at their leaf structure. A tea leaf has two internal layers called mesophylls. The upper one is called palisade mesophyll. It serves two main purposes. One is ensuring protection from sun and cold damage. The other is storing various compounds (like chloroplasts) related to tea's aroma. The thicker the layer, the stronger the aroma and the better the protection from weather variations. On the lower part, there's another mesophyll layer called spongy mesophyll. Its role is to store taste-related components. A thick, spongy mesophyll layer contains an abundance of taste-related solids and evokes a more robust, bold, and pronounced taste.

A small-leaf variety tends to have a thick palisade layer and a thin spongy one. It is therefore well protected against sun and cold damage. At the same time, a thin spongy mesophyll layer calls for a subtle, more delicate taste in comparison with a big-leaf variety.

Camellia Sinensis var. Assamica gets its name from the Assam district in India, where it's widespread. Despite its name, the Assamica variety is thought to originate in the area around the Tropic of Cancer in Southeastern China, spreading outward to India's Assam. Currently, it grows mostly in tropical and subtropical regions, including China's Yunnan and neighboring Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam.

The region of and around Yunnan has a 2000-year history of cultivating and producing tea. It is renowned as one of the ancient cradles of tea cultivation. The big-leaf variety in Yunnan is used to produce some bold-tasting black teas as well as the iconic Pu-erh.

Now, let's look at the leaf structure. Unlike its small-leaf cousin, the big-leaf variety has a thin and delicate palisade mesophyll. Thus, they can easily burn in the sun and do not tolerate cold temperatures. On the contrary, their spongy mesophyll layer is dense and thick. The large amounts of catechins inside add to the tea's bitterness and astringency. In addition, during the oxidation process, they transform into other compounds that make the taste and the color of the tea brew bolder and more intense – think aged Pu-erh and Dian Hong cha.

Beyond Sinensis and Assamica – the distant tea cousin

Camellia Taliensis, also known as Dali tea (大理茶), is a small evergreen shrub used for tea production. It's a wild relative of the Camellia Sinensis species, primarily found in Yunnan province, China. The species, known by various names including Wild tea and Dali tea, grows 2-8m tall with distinctive creamy white flowers resembling a fried egg. Its natural habitat in southwestern Yunnan, Thailand, and northern Myanmar faces threats from habitat fragmentation and overpicking.

Camellia Taliensis has larger leaves and a similar chemical composition to C. sinensis var. Assamica. Like all the varieties under the Camellia Sinensis species, it contains both L-theanine and caffeine. Farmers harvest it in early spring to make white, black, and pu'er tea. Notably, Yue Guang Bai ("Moonlight White") is a white tea often made from this plant. Some Pu'er teas from Camellia Taliensis are known to fetch higher prices than those from Camellia Sinensis.

The non-caffeinated tea family

Good news for the caffeine-sensitive souls out there – in recent years, a number of naturally caffeine-free tea species have been discovered that hold a huge promise for the whole tea industry! The trouble with caffeine is that many people who otherwise love the drink are too sensitive to it. In order to remove caffeine from tea, it has to either undergo an immersion in carbon dioxide at very high pressure or scald the leaves with hot water; either way, the most delicate compounds will be affected, be it for the taste or the health benefits they provide. A naturally decaffeinated tea solves all these problems while retaining 100% of the flavor!

At present, a number of tea plant species claim to contain negligible amounts of caffeine – or none at all. One of them is Camellia Crassicolumna, also called "thick shaft tea" (厚轴茶). It is a wild relative to the Camellia Sinensis species, found in Guizhou and (mostly) Yunnan. While its main alkaloid compound is theophylline, it still contains a small amount of caffeine (2-5% of overall content). This species produces Yabao – a bud-only tea harvested in early spring by the local population. The tea it produces has a strong aroma, refreshing taste, and pronounced diuretic effect.

Another decaffeinated species is the Camelia Ptilophylla. Unlike Taliensis and Crassicolumna, this wild cousin to the Sinensis species is claimed not to contain caffeine at all. Instead, it packs 5.9% theobromine – an alkaloid found in cocoa. Thus, it has become famous as "cocoa tea" in the province of Guangdong, where it was first discovered. Its fruity and floral taste, along with the orchid fragrance with dry-fruit accents, make it a great alternative to the local Dancong Oolong tea for those who cannot tolerate caffeine. Additionally, the tea from Camelia Ptilophylla is claimed to have other health benefits, including a protective effect on the cardiovascular system and a beneficial impact on patients with metabolic syndrome.

Another caffeine-free variety, known as Hongyacha, also created headlines upon its discovery in the Chinese province of Fujian in 2018. It was reportedly very different from the Cocoa Tea from Guangdong both morphologically and by its biochemical content. Its main alkaloid is Theobromine, while caffeine is absent.

Exploring the world of tea plants reveals a rich diversity beyond the familiar Camellia Sinensis. From the resilient Assamica variety thriving in tropical climates to the cold-loving Sinensis, and the intriguing caffeine-free Hongyacha, each variety contributes uniquely to a vibrant landscape of the tea plant. A daily discovery awaits in the subtle flavors of green tea or the robustness of black tea, where understanding the origins and characteristics of these plants enhances our appreciation of every sip. The story of the tea plant species is as complex as the flavors they imbue, rooted in history, culture, and the very soil they spring from.